After every flight with my students, I write takeaways noting what needs improvement. While teaching tailwheel flying, noting key moments after each flight allowed me to identify the reasons that kept preventing great landings. After 5 years of doing that, I started to note patterns, which I grouped into 5 key points to achieve great landings.

Will this be applicable to me? These keys are for butter like landings in any airplane, which are different than maximum performance landings.

1. Hold your final approach speed until the round-out

Have you ever felt like the landing happened to you, instead of you making the landing?

If you let your airspeed decrease, the time you’ve got to get ready to land and the rate at which everything happens may leave you behind the airplane.

To have deliberate control throughout the entire process, we must stick with the airplane. But before we can stick with the airplane, we must develop our reaction time and focus. Just picture the amount of changing information we must process in a matter of seconds and even milliseconds while working to land. Whether you realize it or not, you are forced to make decisions very quickly. And the pace just keeps increasing throughout the landing process. Can you keep up?

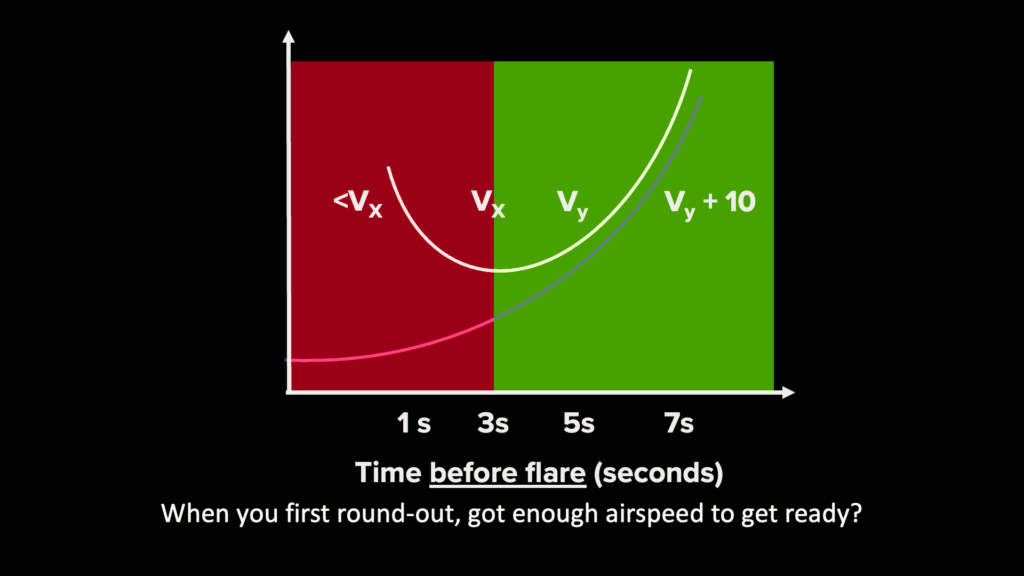

The following graph shows the relationship between the time you are given to “get ready” before the pace starts to pick up speed.

The speed you carry when you first round out to fly over the runway determines how long you will “float” without having to do much. If you arrive at the runway at Vy, you get about 5 seconds before everything starts to change quickly. During this time, you can let the airplane “float” while dissipating speed, much like a bike gliding as you decelerate without effort. The handling of the airplane changes gradually, becoming more demanding as we slow down. Eventually, induced drag increases exponentially and we no longer “float”. Soon, our full participation is required, and we begin to flare.

If you arrive at the runway at Vx, you are immediately placed at a point where the airplane’s handling is changing quickly, with induced drag already increasing exponentially, and less than 3 seconds before it’s time to flare. It’s like jumping on a treadmill that’s already running fast.

Given enough runway distance, arriving at the runway at Vy or Vy + 10 gives you the time to develop touch and deliberate control before the task becomes demanding.

2. Fly the round-out

The round-out begins when we transition from a descending flight path to flying over the runway at a constant height. During the round-out we allow our airspeed to decrease while we maintain a constant height over the runway. When we first round-out, we have enough airspeed to “float” over the runway without doing much. So, fly the round-out, being patient as you slow down.

3. Control rate of descent

If you want to make a butter like landing, what is the rate of descent you are aiming for at the touch down moment and how does it look like?

It looks like an airplane flying a line just a few inches above the runway, where that line gradually blends into the runway, with a rate of descent close to zero. The round-out allows you to capture this line. As soon as you capture this line, get to work towards nailing the goal to control rate of descent. You may also pretend you are doing a constant height low pass over the runway, only a few inches over the runway.

4. Settle a few inches over the runway

Can you settle something gently onto the ground from 5 feet up? Of course not—you need to be just inches above the surface. The same is true when landing: to let the airplane settle smoothly, you must bring it down to just a few inches above the runway before allowing it to make contact.

5. Feel and watch the flare

So you held your final approach speed till the round-out, you started the round-out to capture a line over the ground, and you flew a constant height a few inches over the ground. What is happening? Speed is decreasing and the airplane wants to settle down.

Alertness is key to recognizing the right moment to begin the flare. When you first round-out, notice how the airplane just wants to go forward, but as it loses energy, that forward tendency begins to shift downward. Pay close attention: the first moment you sense the airplane starting to settle or sink, rather than simply carry forward, that’s your cue to begin the flare.

Each time you sense the airplane wants to sink, apply just enough input to keep the rate of descent or vertical speed close to zero. You don’t have to do much, but the input must be immediate. After each small input, the airplane will carry forward again until it begins to settle once more. Early in the round-out, you may have 3 seconds between inputs, but as airspeed decreases that interval shortens: from 3 seconds, to 2, to 1, to less than a second—eventually down to milliseconds.

If you rely more on visual cues than on kinesthetic feedback (the sensations of movement you feel in your body), you can simply use your eyes, especially your peripheral vision, to maintain a constant height over the runway as the airplane bleeds off airspeed. This visual focus often leads you to make the right inputs at the right moments. Over time, it also helps you develop the sensitivity to detect even the slightest forces and accelerations with your body.

This is the time to feel and watch everything the airplane wants to do, to be patient, and let the airplane respond.

Bonus: Don’t mess up a great landing

Always have a target landing attitude for the time you’ll make contact with the ground. Airplanes cannot exceed certain pitch angles—know your maximum allowable pitch and never exceed it. If landing with a crosswind, your target landing attitude will most likely include a bank angle.

Another common way to mess up a great landing is moving the stick when the airplane doesn’t need you, or re-moving the stick when the airplane needs you.

Quoting Jim Lee Alsip: “Don’t wiggle the stick and mess up a great landing.”

Resist the tendency to wiggle the stick. It’s a bad habit if you are doing it for no reason. When you move the flight controls, you command change. The whole point of flying a stabilized approach is to have the airplane established and steady just before landing. Why would you mess that up by moving the flight controls when you don’t need to?

Got any notes that could save the rest of us from bouncing down the runway? Drop them on the FlyORKA app whether you grease your landings or mess them up!

Download the FlyORKA app on Android or iOS and document every landing you butter!

thanks to the author for taking his clock time on this one.